Editor's note: Health inequities have long been an issue for people in the LGBTQ+ community. We're pleased to share a post from our colleagues in Corporate Learning at Harvard Medical School focusing on solutions that health care leaders can champion.

Health care business professionals can improve patient outcomes and reduce health inequities by championing the health care needs of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and/or questioning, intersex, asexual, and two-spirit (LGBTQIA2+) community. These issues are an important priority for health care professionals year-round, not just during Pride Month.

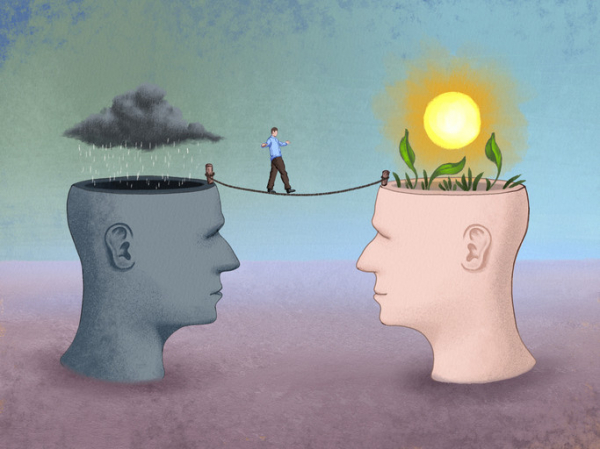

Research shows that the LGBTQIA2+ community faces disproportionate adverse health conditions due to health inequities. It’s important for those working in the health care industry to be aware of the challenges the LGBTQIA2+ community faces to help make systemic changes and improve health outcomes.

The LGBTQIA2+ community — which is less likely to trust the health care system — is a rising part of the population. The 2022 national Gallup survey shows that at least 20% of Gen Z identifies as LGBTQIA2+. This includes our coworkers, customers, and clients, says Dr. Alex Keuroghlian, a psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital and faculty advisor for LGBT and Allies at Harvard Medical School (LAHMS).

“LGBTQIA2+ people experience pervasive stigma and discrimination, as well as numerous adverse social determinants of health, all of which negatively impact health outcomes,” says Dr. Keuroghlian. “Health care professionals, organizations, and governmental agencies need to intentionally provide clinical care and design health systems and policies, in a manner that is culturally responsive and improves health outcomes for LGBTQIA2+ people.”

Due to the politicized nature of these issues, health care providers around the world, including in several U.S. states, face limitations and backlash when providing gender-affirming care. In some places, Dr. Keuroghlian says, “legal restrictions on access to gender-affirming care create challenges for clinicians to deliver this care and for transgender and gender diverse people to safely receive it.”

Everyone in health care — including health care business professionals — can work to improve health outcomes and decrease inequities. “It is critical for all businesses to offer welcoming, inclusive, and affirming work environments and service delivery for LGBTQIA2+ people,” Dr. Keuroghlian says.

Supporting LGBTQIA2+ health begins in the workplace

With thoughtful action, health care business professionals can contribute to greater health equity for these underserved individuals. Some ways to do so include:

1. Take an active interest in better understanding the needs and perspectives of the LGBTQIA2+ community.

Conducting research, including surveys and consumer focus groups, is a good way to help better understand specific health needs and priorities. “This community has historically been excluded from studies and research that would be very helpful in understanding their needs and their challenges,” says Dr. Enrique Caballero, an endocrinologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the faculty director of International Innovation Programs in the HMS Office for External Education. “We need to get to know the population better.”

2. Prioritize inclusive language.

Whether you are involved directly in care delivery or other aspects of health care, pay attention to the words you use — for both customers and employees. Gendered language in job postings, informational or marketing materials, and even casual conversation can be off-putting. That means lost opportunities for organizations and LGBTQIA2+ individuals. Slight shifts in language and conscious efforts like adding pronouns to your email signature speak volumes.

3. Train staff to be community allies.

Gaining awareness of our unconscious biases and making shifts in our everyday language doesn’t happen overnight. Health care industry businesses can help their staff be better allies to the LGBTQIA2+ community by providing access to workshops delivered by community members.

“No one becomes fully competent after one conversation, lecture, or video,” Dr. Caballero says. “It’s a lifelong process in which we all learn how to be more respectful, inclusive, and to embrace diversity.”

4. Support companies and community organizations that focus on LGBTQIA2+ health.

Show, don’t tell. Making financial contributions to organizations already on the ground and working with this population demonstrates that you aren’t just concerned about the bottom line. You are truly dedicated to helping the LGBTQ+ population access good health care.

5. Hire LGBTQIA2+ staff.

The best way to ensure your company is prioritizing health equity is by having a diverse group at the decision-making table. It is crucial to have employees that represent the diversity of your customer base — not only diversity in gender expression and sexuality, but also diversity in race, ethnicity, age, ability, and beyond.

“Part of our obligation is to really open the doors for everybody,” Dr. Caballero says. “Talent is not exclusive to a particular group, and I think that is important to embrace as an organization.”

6. Include LGBTQIA2+ representation in all communications.

Diverse representation is key. Make a pointed effort to include same-sex couples, non-traditional family units, and transgender and non-binary individuals in all kinds of communications, participating in everyday activities.

7. Acknowledge any missteps.

On an institutional level, company acknowledgments can go a long way in rebuilding trust with the LGBTQIA2+ community. Within the organization, it’s valuable to encourage ongoing communication about company culture.

“All organizations should have a system in place for people to provide feedback on how things are going and to report anything that they want to call the leadership team's attention to,” Dr. Caballero says. “Having a system that truly listens to members of the organization — and being sure that follow-up action is taken — is very important.”

8. Make action consistent beyond Pride Month.

Embracing the LGBTQIA2+ community consistently and with commitment all year long “is truly an opportunity for everyone,” Dr. Caballero says. “This is not good just for the members of the community, but for everybody that works in a place that embraces diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

Industry professionals turn to HMS for custom corporate learning programs, including on topics like LGBTQIA2+ health, that leave a lasting impact on participants. To provide these programs, HMS leverages faculty expertise from throughout the School and the entire Harvard University community to share with health care teams. To learn about HMS Corporate Learning custom programs, read about the approach or hear from clients themselves.

About the Author

Corporate Learning Staff

Harvard Medical School’s Corporate Learning solutions provide emerging and established companies with the knowledge they need to address the industry's toughest business challenges. Their extensive portfolio of learning solutions helps teams achieve their potential by advancing … See Full Bio View all posts by Corporate Learning Staff